Reduced inequalities

Unequal countries in an unequal world

Inequality pervades the modern world, both within and across countries, and in terms of resources and opportunities. SDG 10 seeks to address these disparities in both economic and non-economic spheres of life.

The focus here is economic inequality, measured in monetary terms adjusted for price differences across countries. This may seem a narrow lens through which to view a complex phenomenon, but monetary inequality reflects, reinforces, and drives other non-economic inequalities. It is also well-measured, with data going back several decades.

All countries exhibit inequality—but some more than others

Unlike in other areas of sustainable development, there is little consensus about the ideal amount of economic inequality. So, while SDG 10 aims to reduce economic inequality, it does not specify a target.

It is instructive, however, to consider as a baseline a hypothetical society in a state of perfect equality.

Source: World Bank PovcalNet

Imagine a country with exactly 100 citizens, and exactly 1,000 units of income.

Under perfect equality each citizen receives exactly 10 units of income.

If we divide people into groups, each containing one-fifth of the population, each group gets exactly one-fifth of the income, too.

The first two-fifths of the population—"the bottom 40 percent"—gets exactly two-fifths, or 40 percent, of total income. People in this group are a particular focus of SDG 10.

Of course, in this imaginary economy the bottom 40 percent is arbitrary since everyone receives the same income. But in real economies, the share of income received by the bottom 40 percent is always less than 40 percent. That share is one measure of inequality.

Let's see how the bottom 40 percent fared in two real-world economies in 2017.

In Brazil, the bottom 40 percent received much less than an equal share of income: only 16 percent.

We can highlight where Brazil's 2017 income distribution deviated from perfect equality, and by how much.

These highlighted units of income reflect the relative amount of income that is unequally distributed in an economy.

Finland had a flatter, more equal income distribution than Brazil. The poorest 40 percent of Finns received a larger share of total income (28 percent), though still short of the 40 percent they would receive in a perfectly equal economy.

Once again, we can highlight how Finland's income distribution differed from perfect equality.

And we can see that on this measure, Finland is a more equal society than Brazil.

In practice, economists use more complex measures of inequality, such as the Gini index. Different measures emphasize different features of the income distribution. Inequality, even reduced to a narrow focus on income, cannot be completely described by a single number. Depending on the measure used, the ranking of countries might change, but overall patterns and major differences—such as Finland being more equal than Brazil—tend to persist.

The bottom 40 percent: disproportionately young, rural, and less educated.

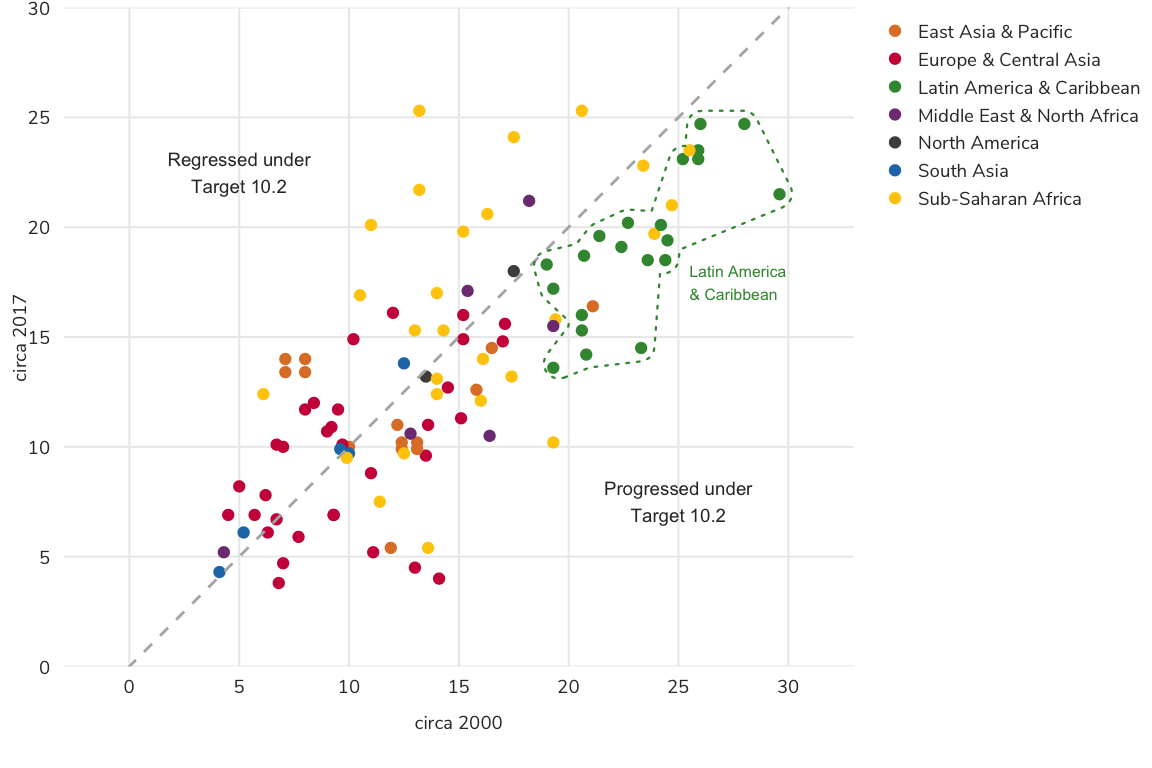

People in the bottom 40 percent differ from the overall population not only in their incomes but also on a range of other characteristics. Certain subgroups tend to be overrepresented—a concern for SDG target 10.2, which emphasizes the economic inclusion of all, "irrespective of age, sex, disability, race, ethnicity, origin, religion or economic status."

In most countries, people with no education or with only primary education are more likely to be in the bottom 40 percent of the income distribution. In many countries, people in rural areas are more likely than people in urban areas to be at the bottom of the distribution. Younger people (under age 15) are more likely to be in the bottom 40 percent everywhere, but older people (over age 64) may be over- or underrepresented, depending on the country.

Gender is the only measured characteristic to have little bearing on a person's chances of being in the bottom 40 percent. But this is complicated by the design of income and consumption surveys, which generally treat the household as a unit, and so cannot measure inequality within households. More detailed research suggests that intrahousehold inequality in consumption occurs and can have serious consequences for the wellbeing of women and children.

How likely is a person to be in the bottom 40 percent of the income distribution in his or her country?

Note: Education subgroups are limited to people age 15 and older. Includes 124 economies with data from 2012 and later.

Source: World Bank Poverty and Equity Briefs. Adapted from fig 2.1 of World Bank. 2020. Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2020: Reversals of Fortune. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Every country can reduce inequality

SDG target 10.1 is for all countries to “progressively achieve and sustain income growth of the bottom 40 percent of the population at a rate higher than the national average.”

When this target is met—when the bottom 40 percent’s income grows faster than the national average—the share of total income accruing to this group increases, the income distribution flattens, and inequality declines (on this measure, at least).

Not every country has recent, comparable data to evaluate this. For the most recent period, 2012–17, data were available for 91 countries covering 60 percent of the world’s population. We can divide them into three groups.

The first group, of 44 countries, experienced growth in both average income and the income of the bottom 40 percent, and the latter grew faster. The difference between the two growth rates—shown by blue shaded bars—is known as the shared prosperity premium. A positive shared prosperity premium means that SDG target 10.1 was achieved in that period.

About half of the countries with data had positive growth and a positive shared prosperity premium

Annualized growth rate, national average, and bottom 40 percent, circa 2012–2017 (%)

Source: World Bank Global Database of Shared Prosperity (7th edition)

The second group, of 24 countries, experienced positive growth but with a negative shared prosperity premium—indicated by red-shaded bars. For these countries, which included many high-income countries, the income of the bottom 40 percent grew but more slowly than the national average, so inequality increased. Income growth might be positive, but these countries nonetheless failed to achieve target 10.1 during this period.

For 24 countries, inequality widened even as incomes grew

Annualized growth rate, national average and bottom 40 percent, circa 2012–2017 (%)

Source: World Bank Global Database of Shared Prosperity (7th edition)

For the third group, of 21 countries, growth for either the bottom 40 percent or the national average was negative. Some of these countries—such as Botswana and Bolivia—had a positive shared prosperity premium but declining average income, leading to an unsustainable situation. For other countries—such as Uganda—things were worse: average income fell, and the income of the bottom 40 percent fell even more.

In the remaining 21 countries, either average or bottom 40 growth was negative

Annualized growth rate, national average, and bottom 40 percent, circa 2012–2017 (%)

Source: World Bank Global Database of Shared Prosperity (7th edition)

Changing inequality among countries paints a mixed picture.

SDG 10 aims to reduce inequality not only within countries but also among countries. While within-country inequality is important, it can obscure the even greater income inequality that persists across countries.

To see how inequality across countries has changed over the long run, consider the position in 1993 of all the countries with data.

Note: Deciles are constructed independently in each period (i.e., anonymously), such that countries that were in a given decile in 1993 may be in a different decile in 2017.

Source: World Bank PovcalNet

In 1993, Brazil's median income was $5 a day. It's 10th percentile income—representing a relatively poor Brazilian—was $1 a day, while it's 90th percentile income—representing a relatively rich Brazilian—was $20 a day.

Finland's median income was much higher—$30 a day. These two distributions barely overlap: a typical poor person in Finland was about as well-off as a typical rich person in Brazil.

In the same way we can plot the 1993 median income and distribution of every country with data.

To see how inequality across countries has changed, we compare median incomes. We focus not on individual countries, whose rise and fall may result from idiosyncratic factors, but on larger groups of countries—deciles—that reflect broader trends.

First, we index each decile (of country medians) to its 1993 level, to focus on the growth that followed.

Over the 24 years to 2017, the deciles experienced different annualized growth rates.

Across all countries, the seventh and eighth deciles—which by 2017 included Azerbaijan, Brazil and Turkey—grew the fastest. Since these deciles grew faster than the lower deciles, inequality increased across the bottom four-fifths of countries.

But this increase in inequality was offset by slower growth in median incomes in the richest countries, such as Italy, Japan and the United States.

While middle-income countries were pulling away from the poorest countries, they were also catching up to the richest countries.

Overall, changes in inequality across countries over the past 25 years is a mixed story.

Inequality—both within and across countries—is a complex phenomenon. It reflects social, economic, and technological forces, some of which are outside a country’s control. But it can be influenced by policy choices: within countries, by policies on taxation and redistribution, and across countries, by policies on trade and tariffs, migration and remittances, and aid. The other targets for SDG 10 address some of these issues.

Learn more about SDG 10: Reduced inequalities

Swipe for the next chart

Notes

- Monetary inequality can be measured as the flow of income or consumption. Richer countries tend to use income as a measure of welfare, whereas poorer countries tend to use consumption. Income is used here to refer generally to either measure, both of which are adjusted for price differences across countries. ↩

- World Bank. 2020. Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2020: Reversals of Fortune. Washington, DC: World Bank, pp. 100–101. ↩

- For a discussion of intra-household inequality, see Chapter 3 of World Bank. 2020 and Chapter 5 in World Bank. 2018. Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2018: Piecing Together the Poverty Puzzle. Washington, DC: World Bank ↩

- This data is based on household surveys. It is not based on a country’s national accounts. ↩